Homicide in England and Wales, Part 7: Homicide enhancers

This is the last in a series of blog posts summarising the nature of homicide in England and Wales. Each post covers a different aspect of homicide, based on data from the Home Office Homicide Index. This post looks at some common enhancers of homicide: drugs, alcohol, mental health, gangs and organised-crime groups. This post is a summary of part of a longer national problem profile of homicide in England and Wales written by me and Prof Iain Brennan.

Enhancers are factors that increase the likelihood of severity of a crime occurring. They intensify existing crime opportunities by making offending easier, increasing the rewards of offending, or otherwise pushing people towards committing a crime. The term enhancers comes from the book Reducing Crime by Jerry Ratcliffe. Common enhancers for many types of crime include drugs and alcohol, technology or design that makes crime easier, situational factors such as how places are managed, and social conditions such as crowds.

I’ve already mentioned some enhancers of homicide in other posts in this series. For example, Part 3 of this series looked at the different weapons and other methods used in homicide.

Homicide is often driven by drugs or alcohol

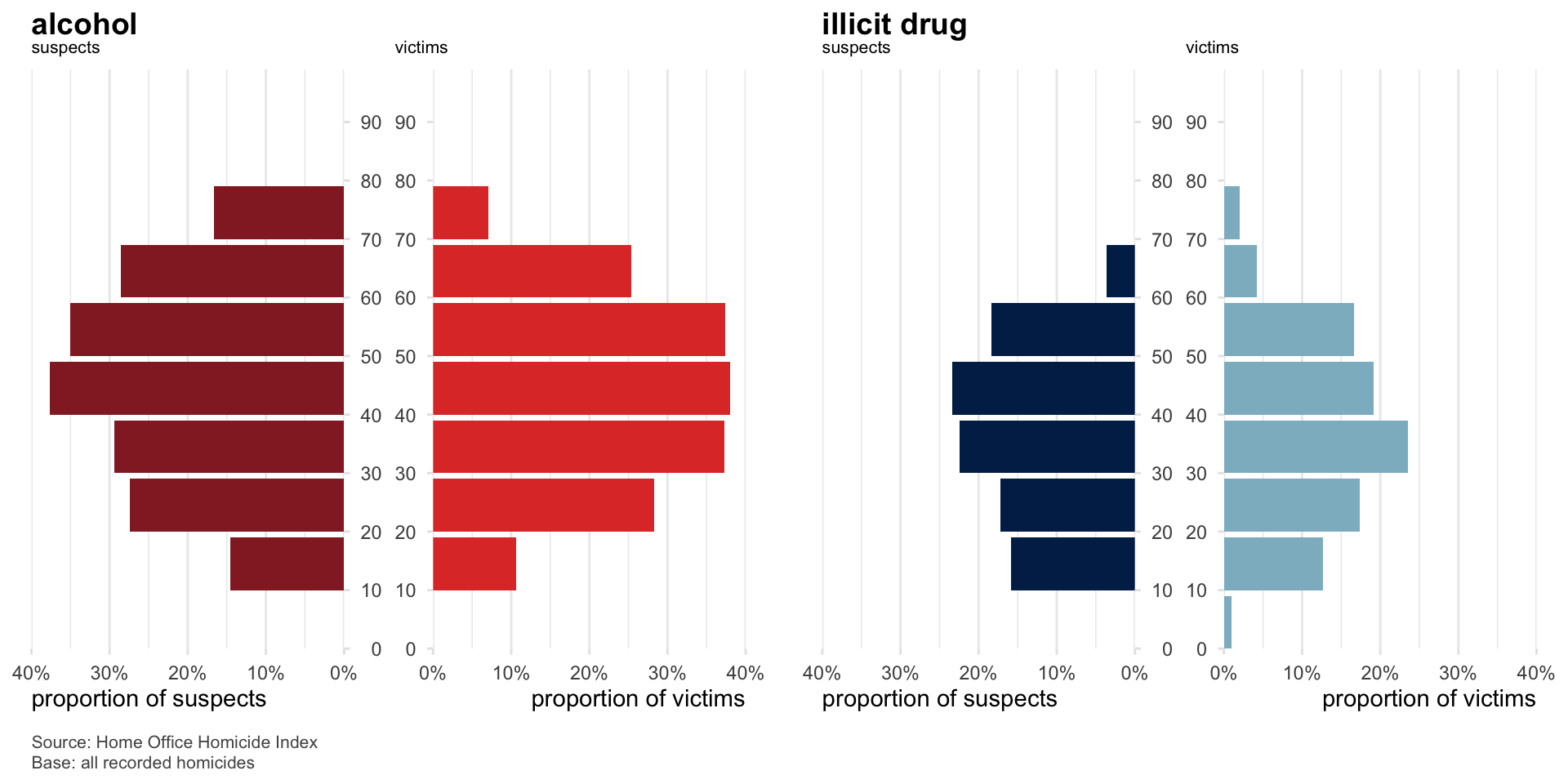

Drugs and alcohol are associated with homicide in a variety of ways. A third of victims were under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol at the time of the homicide: 27% had been drinking alcohol and 15% had taken an illicit drug, while 8% were under the influence of both drugs and alcohol.

Similarly, a third of suspects were under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol: 26% had been drinking and 18% had taken an illicit drug, while 11% were under the influence of drugs and alcohol. Overall, 64% of cases were related to drugs and/or alcohol through either the victim and/or a suspect: 11% were related to alcohol alone, 30% were related to illicit drugs alone and 22% were related to both. Both victims and suspects were more likely to be under the influence of alcohol if they were middle aged, while being under the influence of illicit drugs was more common for younger adult victims (Figure 1).

Victims were more likely to have been drinking in homicides related to fights, brawls, etc. (42%) than in other homicides (27%), while suspects were more likely to have been drinking in homicides related to fights, brawls, etc. (33%) and in domestic homicides (32%) than in other cases (26%). Victims were more likely to have taken an illicit drug in homicides related to a reckless act (34%) than in other homicides (15%), while suspects were more likely to have taken an illicit drug in homicides related to an irrational act (35%) than in other cases (18%).

Homicides are sometimes linked to illicit drugs even when neither suspect nor victim were known to be under the influence at the time of the incident. For example, 34% of homicide victims were known to be users of illicit drugs. While ‘drug user’ in the Homicide Index data is not precisely defined, this is much higher than the 9.5% of all adults who say they have used an illicit drug in the past year1. Drug users were at higher risk of homicide even in cases where it had not been identified that the victim had taken an illicit drug at the time they were killed: 24% of victims who had not taken an illicit drug were nevertheless known to be drug users.

Overall, 64% of cases were related to drugs and/or alcohol through either the victim and/or a suspect

Homicide suspects were even more likely to be known drug users, with 48% of suspects for whom this information was recorded being known to use illegal drugs, including 38% of suspects who were not believed to be under the influence of drugs at the time of the homicide. Among the cases where the drug-user status of both victims and suspects was known2, both the victim and at least one suspect were known to be drug users in 27% of homicides, while either the victim or at least one suspect were known drug users in 53% of homicides.

There was also a clear relationship between suspect and victim drug use: in cases where at least one suspect was a drug user, there was a 57% chance the victim was also a drug user, while in cases where the suspects were not known drug users, there was only a 13% chance the victim was a drug user.

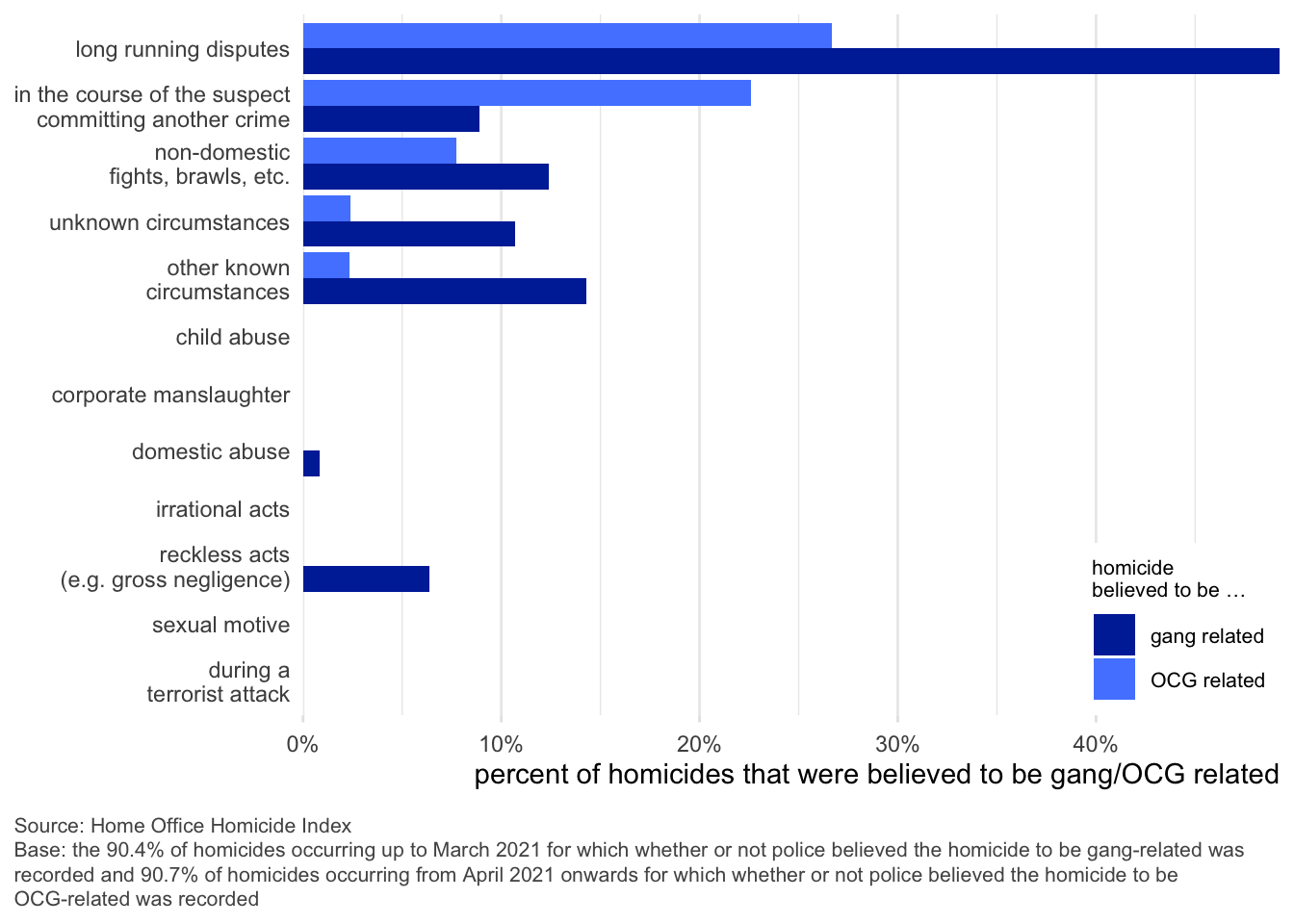

People believed by police to be drug dealers were also at elevated risk of being involved in homicide, either as a victim or suspect: 16% of victims were believed to be drug dealers, along with 28% of suspects. Either the victim or a suspect were believed to be drug dealers in 29% of homicides for which that information was known3, and in 11% both the victim and at least one suspect were believed to be drug dealers. Drug dealers were particularly likely to be victims of homicide in certain circumstances: 54% of people killed during robberies were believed to be drug dealers, along with 43% of people killed as a result of long-running feuds (long-running feuds were also linked to gang homicides – see below).

A sixth of homicides are linked to suspect mental health

Overall, in 17% of homicides the senior investigating officer judged that the homicide was linked to the mental health of one or more suspects. The likelihood of a homicide being linked to the mental health of female suspects was broadly similar whether the victim was male or female, while for male suspects, homicides were more likely to be linked to suspect mental health if the victim was female (29% of such cases) than if the victim was also male (11% of such cases).

Homicides were much more likely to be linked to suspect mental health in some circumstances than others. Mental health was particularly likely to be a factor in homicides related to irrational acts (75% of homicides were linked to suspect mental health) or domestic abuse (34% of homicides). Conversely, mental health was only very rarely a factor in homicides related to the suspect committing another crime (2% of homicides were linked to suspect mental health), reckless acts (3% of homicides were), or child abuse (4% of homicides were).

Homicides were more likely to be linked to suspect mental health in cases that were also linked to illicit drugs. Suspect mental health was a factor in 25% of homicides where the suspect had taken an illicit drug (whether or not they had also been drinking), compared to 15% of homicides where the suspect was not under the influence of drink or drugs, and 14% of homicides where the suspect had been drinking but had not taken drugs.

In summary

Homicides very often involve either the victim and/or a suspect being under the influence of alcohol or illicit drugs. This isn’t surprising: in Part 2 of this series I mentioned that the most-common circumstances in which homicides occur is during fights and brawls, which are often aggravated by alcohol or (some types of) illicit drugs.

Drug users are at much higher risk of being homicide victims than other people in society. Less than 10% of people in England and Wales say they have used an illicit drug in the past year, but a third of homicide victims were known to be drug users and 15% were known to have taken an illicit drug at the time they were killed. People involved in drugs supply were also at very-high risk of homicide, especially where the homicide was linked to gangs or OCGs.

References

Footnotes

Based on estimates of the proportion of people aged 16–59 years interviewed for the Crime Survey for England and Wales who have used an illicit drug in the past 12 months (Office for National Statistics 2023).↩︎

Whether a person was believed to be a drug user or not was recorded for 96.8% of victims and 56.4% of suspects.↩︎

Whether a person was believed to be a drug dealer or not was recorded for 96.5% of victims and 56.1% of suspects.↩︎